The store manager handed me a copy of “Let My People Go Surfing” by Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, and said that it would give me a good foundation for understanding the company and what it stands for. While we were chatting, a well-dressed young woman approached the manager and asked if she could submit a resume because she was looking for a job.

The store manager handed me a copy of “Let My People Go Surfing” by Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, and said that it would give me a good foundation for understanding the company and what it stands for. While we were chatting, a well-dressed young woman approached the manager and asked if she could submit a resume because she was looking for a job.

He politely accepted the CV then asked why she wanted to work for Patagonia.

“I love the sales process and am interested in retail,” she responded. “I have worked in retail for many years!”

“Okay… thanks,” the store manager replied, “we will give you a call and have a chat when we are looking for someone.”

After the prospective employee left the shop the manager turned his attention back to me and softly said “boom-boom.”

“Huh?” I replied. “What do you mean?”

“Oh nothing, really. It doesn’t mean she wouldn’t be good working with Patagonia but saying you ‘love retail’ is not exactly the first thing I would expect a prospective Patagonia employee to say. We are not a typical retail store. Our employees love to find something special for their customers that will work beautifully for them and last for almost a lifetime. We would rather sell them one thing that they love than three things that they will throw away in twelve months. Our employees tend to love the outdoor world whether they are surfers, kayakers, climbers, campers or whatever. Our employees generally like that they work for a company that fights for the environment. That young woman may work for Patagonia someday, but loving retail is only a small part of what we are about.”

The shop manager was dead serious. This was my first clear indication that Patagonia’s branding as an environmentally concerned business was more than window dressing.

The following are just some of the things I discovered about the Patagonia company and its founder when I ripped into “Let My People Go Surfing: The education of a reluctant businessman.”

The young French-Canadian, Yvon Chouinard, moved to California with his family when he was a nipper. Not being able to speak English and having a “girls name” didn’t win him any friends at the first school he attended. Things were marginally better at his next school, though he never took enough interest in his studies to secure solid grades. He did love (and found that he was pretty good at) some of the sports he played at school but discovered that while he was naturally athletic on the practice field, he sucked at organized sports when he had to perform in front of a crowd. This led Yvon to believe that the best sports were the ones that you made up yourself.

Didn’t know what to do with pitons and hammer

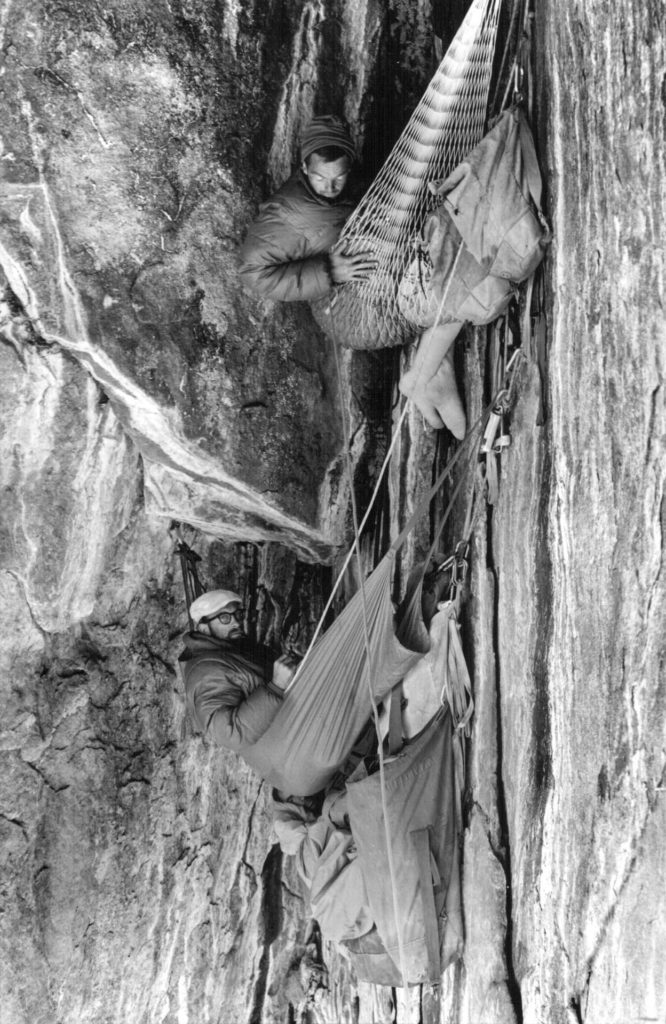

He wasn’t far into his teen years when he discovered climbing. While his first efforts involved climbing down mountains (in search of falcon nests – as a fourteen-year old member of the Southern California Falconry Club) it wasn’t long until he discovered that climbing up mountains was even more exciting. On one early learning trip to the Tetons he was having trouble talking climbing crews into taking him on, given his age and lack of experience, until he discovered that a better strategy was to just keep quiet about his non-existent climbing history. This led to a couple of older blokes teaming up with him to make an attempt at Templeton’s Crack on Symmetry Spire. Despite his never having climbed with ropes before, and not knowing what to do with the pitons and hammer they handed him, he pushed ahead and figured it out as the climb progressed. He even managed to lead the most difficult pitch on the climb.

The next few years found Yvon, still a teenager, seeking out new climbing experiences all over the USA and Canada when the seasons and money allowed. In climbing season, he and his mates learned to get by on less than a dollar a day. Living off cat food (supplemented by the occasional squirrel plus the cheapest root vegetables available) and sleeping under the stars became his chosen way of life for much of the year. He loved it! He was proud of the fact that “climbing rocks and ice falls had no economic value to society.” He was not remotely interested in what society regarded as economically valuable. A desperado! Her likened himself and his climbing mates to a “wild species, living on the edge of an ecosystem – adaptable, resilient and tough.”

Still a young man, in 1957, Yvon found an old coal-fired forge and anvil at a junk store and he set about teaching himself the fine art of blacksmithing. Not happy with the soft European-forged pitons he (and all the other American climbers) were using, at the time, he set about designing and producing a stronger more practical version. When he added a drop-forging die to his collection of smithing implements, enabling him make carabiners as well as pitons, the Chouinard blacksmith operation was starting to grow into a business. He would travel all over the USA, climbing and selling his superior wares from the back of his car during the summer months and work at his smithy shop in winter to create future stock.

Superior quality in terms of design, materials and production were the key principles of his business. Yvon was aware that his own life, the lives of his mates and the lives of other climbers depended on the pitons, carabiners and hammers that he made so he was going to make sure that they were the best they could possibly be. Such determination to produce high quality equipment was not ideal in a financial sense for the young business.

We “showed only a one percent profit at the end of the year,” in those early days, Yvon explains in his book. “Because we were constantly coming up with new designs, we would scrap after only one year, tools and dies that should have been amortized over three or five years.” The shop may not have been making a huge profit, but it was producing the most innovative and strongest climbing implements available – and it was also providing employment for a growing number of Yvon’s Southern Californian surfing and climbing buddies.

Changed the sport of climbing overnight

By 1972, Chouinard Equipment launched an innovation that was to, almost overnight, revolutionize the sport of climbing. For years Yvon had made it his role, as head of his company, to travel the climbing world, seeking out exciting new ideas for new products. By the early seventies he had become increasingly concerned that the pitons that he was selling were destroying the rocky faces and walls that he and other climbers loved. So, in their 1972 catalogue, Chouinard Equipment not only launched their new range of aluminium chocks (hand-placeable and removable chocks that could be wedged into the same cracks and gaps that were being destroyed by pitons) but published a fourteen page editorial that explained the virtues of “clean climbing.” Chouinard Equipment was imploring its customers to adopt a new approached that left the mountains in the same pristine condition they had been in before the climber approached a mountain wall.

Within a few months Yvon had pretty much destroyed the piton business that had been the mainstay of his company but in the process had created a new product that was selling far faster than he could make them.

As the seventies progressed, despite the company dominating the world climbing equipment business, profits were still not that great. Yvon saw an opportunity to support the hardware business by producing and selling climbing clothes. While the intention was to produce outdoor clothes with the same attention to detail, toughness and high quality that characterised the hardware business lessons were learned along the way. The company’s super tough and innovative “rugby jersey” climbing shirts, when initially acquired from sportswear manufacturers, were perfect for the job but when manufacturing was handed over to a company more familiar with creating clothes for the fashion market, quality and toughness plummeted. Chouinard had learned a hard lesson about developing relationships with suppliers who understood his need for high standards. He had also learned that, in his business, sometimes delivery times must take second place to quality standards. Making delivery schedules and creating new “fashionable” outfits might work for the fashion industry but, even if some of his clothing product line is purchased by customers as a fashion statement, in the end a quality product must be provided to the company’s more serious and committed outdoor customers.

As the outdoor clothing product range expanded, and sales grew, the company split into the hardware business (Chouinard Equipment) and the apparel business which the leaders of the company decided to name after the mystical and exotic region of Argentina, Patagonia. Throughout the eighties, the Patagonia clothing company came to be as well known for its innovative approach to design and manufacture as the older equipment business had. Again, just as the concept of “clean climbing” had been launched in a company catalogue, Patagonia introduced its concept of “layering clothing” for back country comfort and safety in its catalogue. The layering concept meant wearing an undergarment that transported moisture away from the skin underneath a middle layer that insulated the body and topped off with an outer shell that shielded the body from wind and moisture. Throughout this period the Patagonia research and development teams worked with customers and suppliers to continually improve the product’s performance and to eradicate issues that arose out of the launching of each new undergarment, fleece jacket or shell top.

Jacket made from toilet seat cover

One of the most innovative products launched in this period was the companies first pile (fleece) jacket. The company had wanted to emulate the warmth of the traditional wool garments already worn in the mountains but avoiding the water absorbing problems that such fibres had. The problem was finding a fabric that would do the job. Malinda, Yvon’s wife and business partner (who had become one of the business’s most valuable talents), discovered a polyester pile fabric made by a company called Malden Mills that had been developed as an ideal toilet seat cover. The toilet seat cover jacket originally created by Patagonia was so warm, comfortable and water repelling that it, with multiple generational improvements over the years, has become the mountain standard that still exists today.

Not only was Patagonia innovative in terms of the products it produced but its way of doing things was totally different. People who worked at Patagonia wore to work what they felt comfortable in. As Yvon said “I wanted to distance myself, as far as possible, from those pasty-faced corpses in suits I saw in airline magazine ads.” The same rules applied to staff. Additionally, if there was great surf running, or powder snow after a storm or a family matter to attend to then those needs of employees had to be part of the Patagonia way of life. The company recognized that “work had to be enjoyable on a daily basis” and that the distinction between work, play and family should be a blurred one.

Between 1980 and 1990 the Patagonia company grow… and grew… and grew. Sales rocketed from 20 million annually to over 100 million. Patagonia, with all its modern ideas about management and product innovation had become a raging commercial success!

In line with sales growth, staff numbers were expanded dramatically but, while, in many ways, the company was innovative in its product development approach and overall philosophy, its strategies in relation to investment, financing and growth mimicked more traditional mainstream US businesses. With the early 1990’s business slowdown, Patagonia’s sales continued to grow but at a far slower pace than they had been growing in the past and at a slower pace than the company had been gearing up to deal with. Potential disaster was at the door.

Despite laying off staff being the company’s biggest nightmare the reality was that the staff numbers had been increased to take advantage of sales and growth that was just not there. There were more people than there was work to do. Not only did the company need to down-size but it had to take a hard look at every aspect of the way it did its business if the company were to survive and prosper into the future.

Crisis meetings between company leaders, the Chouinards and other trusted employees raised the critical issue of what kind of company they wanted Patagonia to be. We want to be “a billion-dollar company… okay… but not if we had to make products, we couldn’t be proud of,” was the response tha came out loud and strong. Discussion also centred around what Patagonia could do to stem environmental harm done by the company. There was also much talk about the common values all Patagonia people held and why they had all come together in the first place.

A range of practical actions arose from these crisis talks. Critically, a set of “philosophies” were developed for each of Patagonia’s operational functions (product design, production, distribution, marketing, finance, human resources, management, and environment). Instead of having an “operations manual” that set out mandatory processes and pat answers to operational questions these philosophies would enable Patagonia people to ask the right questions to come up with answers that reflected the values and ambitions of the company and its people!

A stated mission!

To bind the company philosophies together a company Mission Statement was created.

“Make the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, and use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”

No dodgy assumption here that an organization’s primary “raison d’etre” is to optimise capital returns for investors, shareholders, and other stakeholders. This statement makes it clear that Patagonia exists to do good. There is a good-natured determination in the mission. It’s not enough to simply aspire to make organic products, for example. Some organic textiles and fibres are extraordinarily damaging to the environment through their excessive use of water in production. Neither is it just a simple matter of swapping over to a superior synthetic product that uses less resources in its production. If one must use synthetics, then it is best to use synthetics that are recycled (Patagonia’s synchilla fleece jackets, since 1993, have been manufactured exclusively from recycled soft-drink bottles). Patagonia not only seeks to provide the best quality products to its customers that do as little as possible damage to the environment, but it seeks to make money that can be poured back into environmental causes. While Patagonia, as early as the late 1980s had pledged 10 percent of its profits to funding grass roots environmental causes, by the mid 90’s the company raised the bar even higher by pledging 1 percent of its total sales revenues to the environment. Charitable pledges on profits give a company an easy way out if the organisation is not making money. With Patagonia, these days, it makes no difference whether the company makes money in a particular year or not. Money is still corralled off to the environment!

Achieving new sales and growth targets is not what gives Yvon and his team a buzz. The fact that the organization has donated over seventy-nine million dollars to environmental activists is a far bigger thrill. For Patagonia, success is not measured in sales targets achieved but in threats averted – in old-growth forests NOT cleared, in mines NOT dug in pristine areas and in toxic pesticides NOT sprayed. Chouinard knows that assisting activists in the stopping of degradation not only limits damage that has already been done but can also help environments to regenerate. When pollutants are no longer being pumped into rivers and where dams are removed from rivers that were once wild, endangered species (fish, animals, birds, vegetation) often storm back!

Central to Patagonia’s 1991 action to change the company’s direction was its commitment to walk away from the typical corporate insistence on seeking quarterly growth. Chouinard and his team committed to a new approach to company planning modelled on the Iroquois people’s decision-making philosophy that involved keeping the needs of seven generations in the future in mind. The Patagonia team want their organisation to still be around, still doing important work, in one hundred years’ time, and all planning decisions should (rather than focusing on the next financial quarter) reflect that desire!

Since the horrors of 1991 when Patagonia had to dramatically shake up its approach to the business world (and to accept that its worst nightmare of having to lose staff had come true), the turn-around has been massive. With its eyes firmly set on its mission and its operational philosophies along with a commitment to not be waylaid by the temptations of seeking perpetual financial growth, life at Patagonia has become way “less interesting” for Yvon Chouinard and his team. They are just trying to live up to their mission and common values.

Taking responsibility

These days the focus is on “cleaning up our supply chain including the use of organic natural fibres and recycled synthetics, less toxic dyes and chemicals, better labour practices and taking responsibility for our product from birth to rebirth.”

Patagonia and its sibling company, Chouinard Equipment, had always been great companies… innovative and ethical companies with great products and a great social conscience. But it took the business shake up of the 1990s to focus the attention of Patagonia on an ideal approach and true purpose. Its leader, Yvon Chouinard, discovered that “the things that he learned as an individual – a climber, a surfer, a kayaker and a fisherman were the same things he needed in a business philosophy. Live life simply – eat lower on the food chain – reduce consumption of material goods – do high risk sports but don’t exceed your limits – push the edge of the envelope and live for those moments on the edge but don’t go over. Be true to yourself. Know your strengths and weaknesses and live within your means.”

Next time you wander into a Patagonia retail store don’t expect to be hounded by a sales-driven retail-loving sales assistant who will want you to purchase a complete outfit. It’s more likely you will find a crew of like-minded individuals who are committed to the environment and committed to helping you find something that will suit your needs precisely. If you do buy something special you can be confident that, as you leave the store, you will have taken possession of something that has been created with enormous care to not only optimise your ability to be warm, dry and safe in outdoor and extreme environments but has been created in a way that will minimise harm to that precious environment. You can also rest assured that some of the money you spend will be poured into environmental causes!

Despite the progressive-leaning views that I carried through high school, university and my early business career I was one of many hundreds of millions of young people seduced by the neo-liberal view that the foremost responsibility of any company was to optimise financial returns to my organization and its shareholders. Reading the story of Yvon Chouinard’s life and how his company, Patagonia, have tracked over the years made me ashamed… ashamed that I was unable to see that there were far more ethical and productive ways of living in the business world.

Leave a Reply