“Come on. Get over it. Move on. It’s just a game!”

Most sports lovers have, at some stage of their sporting lives, experienced what they perceived to be a significant sporting injustice and had their complaints answered with just such a response. But is it “just a game?” Do injustices within the sporting realm have the potential to do real damage to individuals and to society. Socrates heard a story about a local sporting team who felt that they had been dudded by the organizers of their regional competition and he wondered whether their concerns about the perceived lack of fairness in their case and the potential consequences for all involved had any merit.

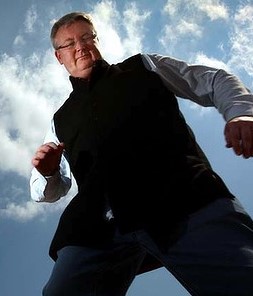

When Socrates heard former rugby referee and philosopher, Dr Simon Longstaff (Executive Director of The Ethics Centre), discussing the importance of ethics with great eloquence and passion on the radio he thought that he might be a good person to ask about whether ethics applies in sport and whether there are potential consequences for society when fair play in sport is sidestepped.

Simon was kind enough to agree to a chat.

Socrates: In what ways can a positive sporting experience contribute to fairer, healthier, and more just communities?

Simon: I think that sport brings a certain kind of reality to day to day experience. If you are living in the current world you are surrounded by advertising, public relations and political spin and things of that kind so you are always a little suspicious of what people tell you – whereas the embodied nature of most sport, where you’re actually there, face- to-face in an individual contest or as part of a team, it’s very hard to hide from the underlying realities of that. When you come to that contest you have in mind, usually, (no matter what level you’re at), that there is a basic framework in which the contest will be fair. That might mean simply that the rules are followed. If you are victorious… if you prevail in the contest (if that’s the point of it) then it’s because you deserved that and you can take some credit for it. Whether it’s due to some physical prowess or mental toughness or character or whatever it is that you may have contributed (or even if its not about winning or losing… if its for the joy of the competition itself) that if that competition itself is good, one of the effective elements of it is that it has been played not just within the letter of the law but within the spirit of it. A fair contest in other senses. I think that that carries through into life because what it does is that it proves that such things are possible. It is an antidote, if you like, to not just the scepticism but to the cynicism of other parts of experience that say everything was rigged. That say nothing can be done that’s fair! That say the strong will always prevail over the weak because some can cheat and get away with it without any consequences! That sporting experience, if you have it, is something that you carry into other parts, so you know that it doesn’t have to be like that. I’ve just come from something that I’ve done where it was fair. That was enjoyable… and that was part of what made it valid in my experience.

If you think that it is rigged, why would you try?

Socrates: To what extent is perception of fairness an important element of sporting contests?

Simon: I think it’s essential. Not just essential for the people who compete but also for those who watch it – so it goes to the point I was making before. If you were a spectator and you thought that every outcome was in some sense rigged, (and that certainly happens when you start to hear about people who might have thrown a contest because of betting or other things like that), then the whole point of it is lost. There is not a real contest. Its all fake. And so that perception matters again even if you are a participant in it. If you think that if it is rigged, why would you try? Why would you do your best and test yourself to the limits if ultimately that counts for nothing? So perceptions of the fairness of sport are absolutely essential to its legitimacy in society which goes well beyond it just being an entertainment. There are lots of things that can entertain. But sport needs to have a legitimacy that is rooted in the notion of fair play. But the perception is only as good as the reality because if you were to confect a mirage, if you like, of fairness around sport where behind the scenes it is actually corrupt… its actually been rigged… that, more than anything else, is capable of destroying it for everybody. So the perception is really important, but it is only as helpful as the underlying reality upon which it reflects.

Socrates: Are there more significant negative outcomes to individuals and communities than mere “disappointment” when a sporting outcome seems unjust? What are some that you can imagine?

Simon: I’ll give you an example. So… lots of people will remember the ball tampering incident involving the Australian cricket team in South Africa and what flowed from that. Now… you can look at that and say… well it’s a group of people who are out hitting a ball with a bat… its not the most significant thing in the world in terms of its intrinsic importance. Playing ball games, compared to things like negotiating peace treaties and ensuring a just allocation of resources in society… things of that kind… had a disproportionate effect in Australia and the reason for that I think comes to your question. Australians had been looking at evidence of unethical conduct… even amounting to corrupt conduct… in politics… and in business… almost like a metaphorical stain that was seeping from the edges and across the continent. But a lot of people held in mind that there was one place where this corruption would never go. And that was cricket. People even used the language “it’s just not cricket”. Cricket is synonymous with fairness. So the impact of the revelation that the Australian cricketers were actually cheating was much more significant than simply the betrayal of a set of rules. It seemed to say to people that there is nowhere in society that is immune from the corruption that is taking place. So it had a devastating effect for many people including people who were literally in tears as a result of that incident that took place. Now I think that that phenomenon, on a national level, can be read into what happens in local communities. If you find that there is this bit of your life that you thought was governed by genuinely fair play is in fact nothing like that at all, and that people are colluding in covering this up, then it causes broader damage within society. Its like the opposite of the first point I made where you experience fairness you take it into your life and say “ah – that (fairness) is possible”, and “(unfairness) doesn’t have to be”. When it’s the other way, it destroys your hope that you can preserve something to believe in – that’s got some kind of integrity to it – and that embodied nature of integrity which is what sport actually produces – so I think that it does have implications for, large scale and small scale, in terms of what people are thinking about their society and their place in it. Not just what takes place on the field of play.

“Show a genuine sense of remorse and intention to learn from it”

Socrates: While individuals (referees, administrators, coaches, athletes etc) will make mistakes how can sporting organizations minimise the impact from situations that seem particularly unjust?

Simon: I am a referee myself. I refereed rugby union years ago. I used to do first grade in Tasmania which wasn’t the world’s best place for rugby, but it was a challenge. You make mistakes. You do! But you have to own them. And you have to own up to them. And apologise. And show a genuine sense of remorse and intention to learn from it. So its about responsibility. Sometimes you have to do that even if no one noticed. That is where responsibility is different from accountability. You are held accountable to other people if they see you do something wrong. Responsibility sticks with you whether there is someone watching or not. You still continue to be responsible. We have to distinguish between responsibility on the one hand and culpability on the other. I was talking to a group of elite athletes about this on Monday morning. The idea that you may be responsible for the thing that happens that loses a game for example in that you don’t execute as perfectly as you should have. But you may not be culpable. You may not be blameworthy for that if you had done all the things that you should haver done in preparation… all the training and other things athletes need to do. So, in that case, you are responsible but not blameworthy or culpable. The same is true for an official. You make a mistake as a referee, player or official where you need to be responsible, but you may not be blameworthy. But if you are culpable… if you have been indifferent or reckless or dishonest or any of those things… then you should pay the price of that because in your taking on a role as a leader, whether its as an official in a match or an administrator (remembering that everyone volunteers for this – no one is tapped on the shoulder and told you must be the referee or official or captain or whatever), then you must know that when you volunteer you accept that you will be held to account and that if you are responsible and blameworthy you need to accept whatever penalty comes to those that betray whatever important ideal has been lost.

Socrates: Would you have any general comments about the “case study” provided? Can you see any potentially negative outcomes arising from such a situation?

Case study: Midway through a regional sporting competition a reasonably strong women’s sports team seemed assured of winning the competition’s fourth semi-final spot in the competition but were performing at a level well below the top three teams. Because of covid19 limitations on the movements of people across borders a number of athletes from a higher ranking professional competition, were cut off by the border from participating in their own pro competition, so, to enable themselves to stay fit and keep playing their sport, they signed up with this fourth ranked amateur team for the remainder of the season. Other teams in the competition grumbled about a selection of elite players joining the one team but made no formal protest on the grounds that the competition was being enhanced by having superior players coming on board. Not surprisingly, the team that acquired the superior players went on to win all of their remaining regular-season games while racking up huge scores at the same time.

The unlucky team that drew the short straw in having to face the “enhanced” team in the semi-finals had been smashed by the pros only a few weeks earlier. The coach of the “unlucky” team, with the help of his senior players, devised an unorthodox strategy to combat the strengths of their opponent’s new elite players. They practiced this high-risk strategy at training over two weeks and shocked all of the remaining teams in the competition when they turned the tables and managed to beat the team with the pro players in the semi-final.

Several days later, after the draw and location for the grand-final had been decided and broadcasted, the team who had beaten the team with the superior players were advised by the competition administrators that, because of a technical error in the filling out of the match sheets and an ensuing appeal by the losing team with the pro players, their team had been disqualified from the competition and that the losing team with the superior players would now play in the grand final. There was never any suggestion that the disqualified team had in any way attempted to cheat or that they were in any way advantaged by the paperwork error. The argument put back to the disqualified team was simply that “rules are rules” and that the beaten team’s appeal must be upheld. The “enhanced” team then went on to beat the team that had led the competition all season in the grand final.

While this local competition does not have any national or even state significance, each of the four clubs involved in the semi-finals would have hundreds and hundreds of registered junior and senior players and many more hundreds of supporters. While the controversial way in which this competition was decided may not be big news or have earth-shattering significance it is likely that the outcome sent all kinds of ethical, cultural, psychological and sociological messages to the clubs/organizations involved (and their players, members and supporters).

Simon: There are a few different dimensions to this. Firstly, at one level you could say that if the team was fairly beaten… that is to say the team that had the star players but nonetheless was defeated believed themselves to be outplayed on the day and it was always open for them to accept that result – not to seek to impose a technical fault on the side that had prevailed – you would think that that was an honourable thing to do because they had been outplayed on the field. Against that, of course is that a club, a sporting club, is more than just the team on the field. It is a compilation of its members, administration, all the different people who come together. If every club is bound by the same basic requirements to meet whatever the technical aspects of playing a match are (in terms of registrations and forms – the bits and pieces) then they should know in advance that the particularity of their conformance with these requirements is every bit as important as the performance of the people on the pitch in the course of a game. The person who errs in terms of the paperwork hazards a result, in the same way that a goalkeeper (in soccer), who doesn’t practice, hazards a result on the field. That is the team effort. It’s not just the team effort of those who were on the field. The team was that group of people playing plus everyone around them in the club itself. In that sense, if they failed to meet the overall requirements then they failed, as a team, to satisfy the requirements for a victory. There are arguments to be said for why it is fair that the side that failed to perform as it should as a whole, including the paperwork was denied because it hadn’t won in all aspects of the game but I think that it would have been an honourable choice for the side with the special players that had been defeated on the field to choose not to press its advantage in that case.

Socrates: What if the official who made the technical error could mount an argument that his error was primarily caused by unusual circumstances surrounding the current coronavirus crisis?

Simon: It is then open to the authorities in charge of the game to take that into account. To find that this is not a fault. To excuse it in the same way that you would excuse other people in exceptional circumstances. The point then is whether or not the jurisdiction within the game acted in a just manner – did they take into account all relevant considerations. And that is a question for them rather than the two sides.

Socrates: According to former federal MP and Minister Robert Tickner, Australian post codes with effective sporting associations statistically have far lower rates of incarceration that post codes that do not. Why do you imagine that this is so?

Simon: Well… a lot of crime and dysfunction involves people who come from environments where they feel they have very little control over their lives and so you will see that there are many social ills. Crime is one part. Not just because there is poverty… people can be poor but very orderly… but there is a sense that they are not connected to others, so they don’t feel a sense of interpersonal accountability… as one person owes a duty to another. They don’t really see each other as fully social people because they don’t relate in that sense. They might be more clannish in that sense that they will seek to do right by their families, but others might appear to be strangers. They don’t have much control over their lives, so you get control by breaking the rules and showing that you have got autonomy. So follows a whole range of difficulties. One of the things about belonging to a sporting club and engaging in sport is that you reverse all those things because you do have a sense of control because if you are playing the game and you know what you have to do and you take responsibility for your conduct there… you do recognize people who you have a connection with beyond your immediate family. People who are part of that club would be total strangers, but you do have a sense of connectedness because you have a shared objective and a shared sense of identity and things like that. So I think all those things work towards a society in which people are far more likely to do the right thing by each other… not because they are going to be compelled by law enforcement or through surveillance or control but because they recognize that people are part of a network to which they belong and they are unlikely to want to act in a way that harms them.

“You are not required, as a player, to be indifferent”

Socrates: Are there practical ways that sporting association and clubs in communities can take steps to optimise ethical behaviour among players, supporters, and officials.

Simon: I think that, in practical terms, they have to talk to them about the importance of it… and use the language of ethics… talk about their values and principles… and stress why they understand that the legitimacy of their sport depends on a collective commitment to uphold these core values and principles that extends beyond just players and officials to the people on the sidelines. There are terrible things you see, for example, from the supporters of football sides – whether its parents at kids sporting matches or of course in the larger scale games. Those people are part of the game… the spectators are part of what makes things happen and they are part of the club’s dealings and share the common obligation that goes with this. I think they should… particularly among players… see themselves as stewards of the game! But if any group is the steward that carries its traditions… its best practices… forward it’s the players. I have often thought, for example, when Adam Goodes had been having all the terrible experiences he had with racism when he was playing with the Swans if both sides just sat down on the pitch and refused to play until that kind of conduct had been eradicated in the stands then it would have had a massive impact because you are not required, as a player, to be indifferent to this. In fact, it is your responsibility… as I say you are a steward of the game! So those are the kind of things that I would do. I’d educate players, fans, and officials about the ethical component… not just the rules… but the spirit! I’d build that! I’d look to make sure that cultures within sporting clubs are practically aligned to what they say that they stand for. To often you will find that sporting codes have all sorts of very grand statements but when you look at the reality about how a club or association operates it’s a million miles away. People say that this is pure hypocrisy. They don’t believe in their own statements! They don’t behave as they say they do! Why should we? And so you can see the cynicism that emerges. It’s a kind of acid that eats away at the bonds of any community and that can happen just as much in sporting groups. Be clear about who you are and what you stand for. Measure whether there are any gaps between your club’s statements and its culture. Talk to people. Talk about the language of ethics. Don’t pretend that’s it’s not important. Make sure that it applies to everybody throughout the network… not just the players and officials but the clubs members… all of them. Give it so its coherent and consistent. That’s what you do then. You build a culture and identity around a club or association or sport where people can say “I feel like that… I can walk to that… can believe in that. It validates who I am, and I feel a strong sense of my identity being affirmed.”

Dr. Simon Longstaff AO FCPA

Executive Director – The Ethics Centre

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organization developing and delivering innovative programs, services and experiences designed to bring ethics to the centre of personal and professional life. Across all our work, the same goals drive what we do: to bring people together, create space for open and honest conversations, and build the skills and capacity of people to live and act according to their values. We remain committed to injecting a pause into the centre of public life and allowing people to stop, connect with others and explore the ethical dimensions of our everyday lives.

Click to visit The Ethics Centre web site

Leave a Reply