One of the most unheralded and beautiful elements of sport… well, of good sport, anyway… is the thing that the Japanese call Ma. Ma, or negative space, as it is sometimes called, is well-known in the spheres of art, design, architecture, drama, dance and music but, when used properly, is also one of the most powerful tools available to an athlete or sports team. This is especially true in association football (soccer). Young soccer players spend many hours practicing their ball skills, footwork, shooting and passing, attempting to emulate the silky talents of Leo Messi, Christiano Ronaldo or Johan Cruyff. While hundreds of hours of practice is critical to achieving greatness, young players should be aware that while technical excellence makes up a large part of the “success” equation it is the vision to see Ma (and the opportunities it presents) that completes the champion player. Players who are great with the ball at their feet… or can pass accurately… or can shoot with great power… but cannot see negative space are just practice field tricksters. Players with a high level of technical skills who can see negative space and exploit it, are potential game-winners.

Ma is not just space. There is space everywhere and much of it is useless. Ma is space that is full of unfulfilled promise. Ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu explained that it is the space within a ceramic pot that makes the pot useful. In a painting it is often the space between objects within the painting that give the painting its beauty. In a beautiful song, it is often the space left between the notes (the pauses) that help to make the song wonderful. This is even so in a powerful speech. It is the thoughtful gaps between the words that often give a speech great meaning and drama! So, its not enough for an athlete to be simply aware of space in their field of activity. An athlete needs to be able see and even create space that is filled with potential, then use their skills to exploit it.

Possession is not the key!

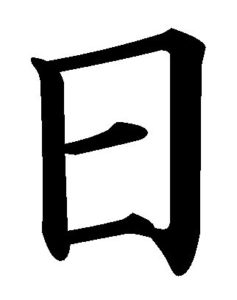

The Japanese character for the word Ma is made up of two other characters. In the Ma character, a gap between two strokes of the pen in the character for “gate or door” is filled with the character for “sun”. Effectively, the design of the character is telling us that Ma is like a gate where rays of sunshine can flow through that gate lighting up the inside. Soccer players must reach beyond their technical skills to create that gate where sporting excellence can flow through. It is not enough for soccer players and teams to use tricky footwork or spectacular passing sequences. There was a time in soccer where many coaches argued that games could be won through weight of possession. Pass the ball around for long enough, be patient, and opportunities will arise was the belief. Great modern football teams have proven that this is not so. A game can be won with little possession so long as the team is capable of identifying and creating Ma and exploiting it effectively. The opposite is also true. Teams with oodles of possession can be easy to beat if their dominance of possession uses space devoid of Ma… i.e. where the ball is shuttled slowly across the field, player to player, or passed backward constantly. Passing the ball to precisely the player and the place where defenders know the ball is going (space without Ma) simply enables the defense to mount pressure on an attacking team. Players and teams must learn to use their eyes and minds to identify Ma and then use their high level of skills to exploit the Ma present for a beautiful and game winning outcome!

In many team sports, a team or player in possession, can threaten their opponent in multiple ways. Some sports talk about a triple threat. The triple threat certainly applies in soccer. When a player is in possession, they must use their wits to determine whether taking on their opponent one-on-one, or passing the soccer ball, or shooting for goal is the more likely to achieve a result for their team. All options are valid, and teams and players should have the willingness and skills to use all three options. To focus too specifically on one approach makes life much too easy for their opponent.

Cruyff’s vision and deception

Dutch soccer forward of the seventies, Johan Cruyff, may not have used the word Ma but he understood the concept and used it powerfully in almost every game. Cruyff, a master of taking on a defender, one-on-one, didn’t just look for space. He used his vision and technical skills to create negative space against a defender. Cruyff’s signature move involved him pulling up in front of a defender (who had seemingly blocked his progress), turning and breaking in one direction to enable him to pass to a teammate on his inside. When his defender committed to follow Cruyff’s move, he would twist his leg around and send the ball in the opposite direction by striking it with the inside of his boot. Cruyff would then pivot and go after the ball which had travelled behind his defender leaving the defender travelling in the wrong direction and completely beaten. While there is technical skill in the “Cruyff turn” it is not the footwork that makes the play so dangerous. The two killers that make the play work are the fake to take the defender away from where Cruyff wants to place the ball and the absence of any “help” defense near the Ma space that Cruyff has created. The “Cruyff turn” is as much about deception and vision as it is about skill.

The ability to create Ma is just as important if a player chooses to pass the ball rather than take on a defender directly. Effective creation of Ma, when passing, is extraordinarily complex in that it demands skill and cohesion between a passer and a receiver. The passer needs to read the movements of the defender and the receiver before placing the ball in the space that will enable the receiver to make life difficult for any defender nearby. To create Ma to receive a pass it is rarely a good decision for the receiver to choose to stay in the same spot as the ball is played to them. If a defender is closely marking the receiver from behind the receiver might choose to fake left, or right, then rapidly break straight towards the passer. The fake, and “lead”, gives the receiver plenty of time to receive a crisp pass in open space before the defender closes down the space between herself and the player now with the ball. If the defender is closely marking the passing lane between the passer and the receiver then the receiver may choose to fake a “lead” towards the passer then, just as the defender has chosen to follow the “lead”, rapidly change direction and head towards the goal. This approach can leave the defender embarrassed and stranded as a “back-door” through-ball to the receiver puts the attacking team in a dangerous attacking position. All of this sounds simple. It’s not. And it takes lots of practice. To create Ma and bamboozle a defender, attacking players who are passing and receiving the ball need to be almost able to read each other’s minds and react with great speed to the feints of the receiver and the movements of the defender. To create Ma, when passing, teams not only need accurate passing skills but excellent anticipation, vision, and deception. Teams need to practice the art of creating Ma through passing to a player creating “a lead” or going “back-door” at almost every training session.

It is extraordinary how often one sees a team losing possession when they have a throw in, all because the ball receivers are all standing around without moving, hoping to receive a ball perfectly lobbed at their feet. Bingo! A defender spoils the party by pouncing on the ball and scurrying off with it. A throw in is an ideal time to put pressure on the defence but potential ball receivers must create the space for the thrower to make life miserable for the defender. Once again, though, it takes lots of practice for receivers and throwers to be able to create Ma and fool defenders, so time needs to be dedicated to it on the training pitch.

Ma is just as important to the player who chooses to shoot as it is to the passer/receiver or player who takes on their opponent one-on-one. Occasionally Ma is created for the potential shooter when they are lucky enough to receive a ball some distance from their defender. In this case, they just need to have the vision to realize that the opportunity is there, and that it is their job to blast the ball into the back of the net. So many players fail to shoot when the opportunity is served up to them. Big mistake. Read the Ma! Always be ready to shoot! On other occasions a defender may be nearby, but she may not have closed down space enough to prevent the shot. The defender may believe that the attacking player may be about to take them on one-on-one… so they are giving themselves a metre or so to react to the attackers move. Again, the shooter needs to read the Ma, and back themselves. Punish the defender’s lack of judgement by shooting!

Part of the goal mouth is the shooter’s space

Ma is also involved in how a shooter aims the shot. Bob Gibson was a highly regarded American baseball pitcher for the St Louis Cardinals back in the sixties and seventies. He said something that soccer players should take note of. The area of the baseball “strike-zone” is causally related to the 17-inch home plate. Gibson used to say, in relation to the “strike-zone”, “the middle twelve (inches) belong to the hitter. The inside and outside two and a half are mine. If I pitch to spots properly, there is no way the batter is going to hit the ball hard consistently.” While a soccer goalie can move around the goal mouth, unlike the static baseball strike zone, the thought that a little Ma space in the goal mouth can belong to a shooter while the rest of the space belongs to the goalie still makes sense. If the goalie is standing directly in the middle of the goalmouth, all of the space that he can cover with a dive is his. The half a metre on the inside of each post (and a reasonable amount of space below the cross bar, too) is the Ma space owned by the shooter. This equation changes as the keeper moves around the goal mouth but the rule that, if the shooter is good enough, there is always space for the shooter still applies. In every practice drill that involves shooting at the goal mouth for a soccer team the attacking players should be allocated a specific target. To simply blast away at the goal mouth during practice ignores the fact that Ma is the soccer players greatest friend!

One of the most beautiful and extraordinary uses of Ma I have ever seen on a soccer pitch did not involve physical space but involved time. Not long ago, the Matildas, the Australian Women’s soccer team, came up against a Chinese team determined to block the Matilda’s progress into the Olympic Games tournament. The Chinese women nearly pulled it off too, as their superior aggression and cohesion saw them leading the Australian women 1 – 0 with only minutes to go. Just when things were looking lost for the Aussies, Kyah Simon managed to swoop on a loose ball in the Chinese box and, in what may go down in Matilda’s history as one of the most extraordinary examples of composure from an individual on the team, managed to bring the ball under control and calmly hold onto it until she had attracted the attention of three Chinese defenders. Only when the defenders were committed, did Simon perfectly lay the ball off to a charging Emily Van Egmond who provided a powerful strike on the ball, beating the Chinese keeper and keeping the Matilda’s Olympic dreams alive.

Ma isn’t always about physical space. It can also be a space in time. Simon’s heroic play found Ma as she almost made time stand still for just a moment. Her “slow-down” play challenged the desperate defenders to see herself as the primary threat leaving Van Egmond with the physical space to work the final miracle.

Very interesting points.